The challenges faced by Filippo Brunelleschi, a goldsmith and clock maker, who went on to become a prominent architect in the Italian Renaissance included politics, wars, and competing interests focused on destroying his credibility. It seems nothing much has changed for innovative project leaders in the intervening 600 years.

Brunelleschi’s primary claim to fame is the design and construction of the dome to complete Florence’s new cathedral. For most of the construction period, the Republic of Florence was one of the wealthiest city states in what is now modern Italy, and to show off its wealth the Republic decided to build a monumental cathedral.

Work on the Cathedral Santa Maria del Fiore started in 1296 under the direction of the Opera del Duomo, to a design proposed by Arnolfo di Cambio. As part of the design process a 30-foot long model of the cathedral complete with its massive dome and ornate finishes had been constructed, and the members of the Opera, and anyone involved in leading the detailed design or construction processes swore an oath to faithfully reproduce the model at full scale.

By 1380 (84 years after the start) work on the body of the cathedral was nearing completion, Arnolfo di Cambio had died, and no-one had a clue how to build the massive dome – it was wider and higher than anything previously built. As a committee faced with a difficult decision, the Opera did what most committees do, nothing! After 30 years of procrastination, a public bid was finally issued in 1418, to find someone to design and build the dome.

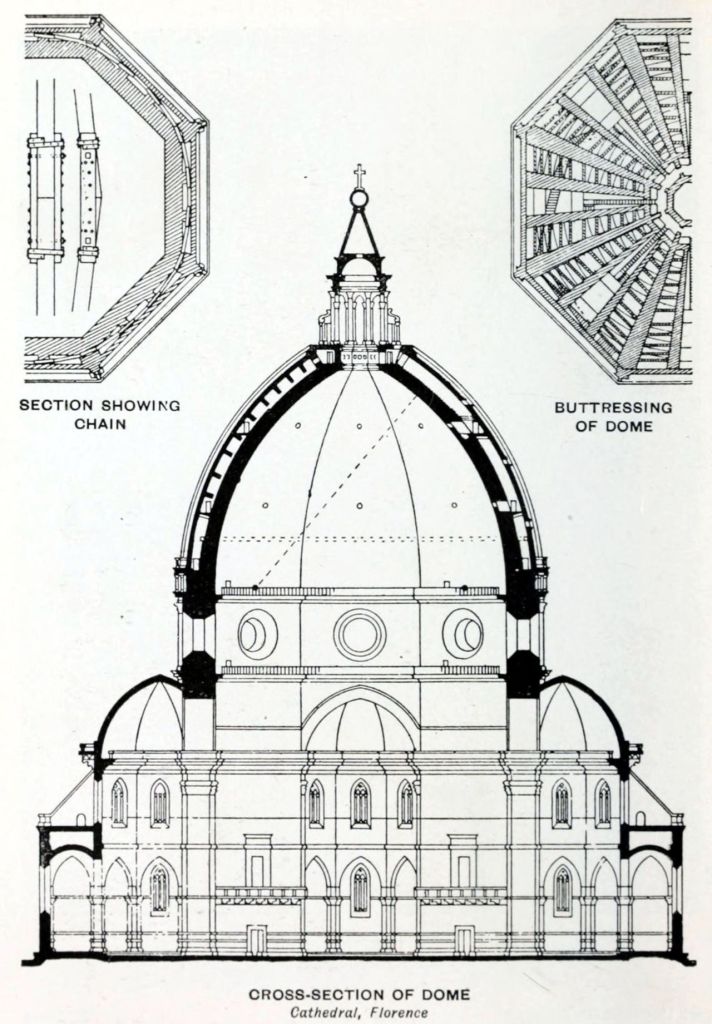

The biggest challenge was the shortage of timber. Arches and domes are traditionally built using centring that supports the incomplete structure until it is joined at the top and becomes self-supporting. However, the size of the dome (143 feet 6 inches in diameter – 46 meters), and the height of the dome, the base started at 170 feet above ground level, meant there were insufficient large timbers in the North of Italy for the work.

The design by Filippo Brunelleschi held the most promise, but it was so futuristic that was almost incomprehensible to the commission members. His proposal was to build the dome without support from the ground. The notoriously hot-headed goldsmith may have won the competition to design the dome for the city’s cathedral, but the way forward was far from clear.

Building a massive self-supporting dome had never been attempted before, and had no formal training as an architect or engineer. He had spent a decade in Rome studying the Roman architecture and construction techniques but the quality of his self-study was unknown.

The novelty of the design, and Brunelleschi’s lack of a track record, coupled to his innate tendency to secrecy, generated perplexity and doubts in the minds of the Opera and so a no-decision approach was adopted. After a year’s delay they appointed two principal construction managers (capomaestro), Brunelleschi and Lorenzo Ghiberti plus two other ‘architects’ as their deputies to design and construct the dome. This arrangement was about as successful as one would expect and after a lot of politicking and intrigue Filippo eventually assumed full responsibility for the construction, but Lorenzo never gave up trying to regain ascendency and the politics and intrigue continued at many levels.

Brunelleschi eventually built the dome between 1420 and 1436, following the design he had presented to the Opera in 1418. The lantern on the top was added some 10 years later following another design competition won by Brunelleschi. His dome still stands in the centre of Florence despite earthquakes, lightening and wars. But why is Filippo Brunelleschi’s successes important?

In my view, there are several reasons. Probably the most significant is the fact that Filippo Brunelleschi was one of the very first master builders and architects to be publicly recognised. He is buried in the crypt of the Santa Maria del Fiore, has two biographies, and is remembered in history – before his time architects and master masons were generally seen as being only slightly more important than other trades.

He also looked after his workforce, wages were set by the Opera and Guilds, but Filippo was responsible for safe working conditions:

- Workers were not allowed to ride in the cranes. Walking up and down 500+ steps may not be fun but it was a lot safer. Riding on crane loads in modern times continued through to the 1970s in most parts of the world.

- The wine workers drank with their lunch had to be cut with at least 50% water. Drinking wine was a lot safer than drinking water in the 15th century, but with a clear drop of 200+ feet to the floor, everyone needed to stay sober. Very heavy fines were enforced if someone broke this rule, in modern times alcohol and drug testing on construction sites is a relatively new innovation.

- The spiral staircases to the dome were one-way, two for going up, two for descending.

- As well as work platforms inside the dome the workers were fitted with leather safety harnesses.

Finally, he was an innovative designer. Detailed designs were drawn, and 3D models made for the complex brick, stone and timber components of the dome, and for the cranes and other equipment used to build the dome. Unfortunately, very little of this work survives, so we still don’t know many of the secrets embedded in the dome’s structure. For the whole duration of the project, Brunelleschi personally managed the stakeholder relationships. With an obviously concerned client, the Opera, he provided detailed information in terms of costs, execution times and the quality of the work. He also managed the relationships on-site with the various master builders responsible for the different sections of the dome, and worked with them to replan the work and resources when necessary to absorb delays. And he had to contend with a population who felt the cathedral needed finishing in a hurry.

The success of Filippo Brunelleschi’s efforts can be appreciated by anyone visiting Florence. If you have found this post interesting, Brunelleschi’s Dome – How a Renaissance Genius Reinvented Architecture by Ross King is a good read.

For more construction management history see: https://mosaicprojects.com.au/PMKI-ZSY-005.php#Process2