As part of the research underpinning our series of articles on the history of railways (and the people and projects that created them), we identified the Diolkos (built in the 6th century BCE) as probably the first purpose built railway used to move commercial ships overland across the Isthmus of Corinth in Greece; see: https://mosaicprojects.wordpress.com/2023/04/17/the-diolkos-the-first-truly-commercial-project/

While the Diolkos’ place in the history of railways (or more accurately guided trolley ways) is not challenged, it seems the innovative approach used by the Corinthians was based on synthesis and elaboration rather than a ‘Eureka’ moment. As this post demonstrates, the use of a man-made structure designed to facilitate the movement of ships across land predates the Diolkos by more than 1000 years. Were the Greeks aware of these earlier developments? Was the Diolkos the result of an inspirational insight, or, as it appears the result of synthesizing a number of ideas from diverse sources to solve a novel problem?

Egypt during the Middle Kingdom

The complex history of the relationship between Ancient Egypt and Nubia (modern day Sudan) goes back millennia and is dominated by wars, conquests (in both directions), and trade; with the Nile being central to all these activities. However, in the ‘border’ region between Egypt and Nubia and extending upstream (South) the flow of the Nile is disrupted by a series of cataracts, the Second (or Great) Cataract being the most challenging for navigation.

The period this post focuses on is during the Middle Kingdom, when Egypt conquered the Nile Vally well to the South of the Second Cataract and built a series of massive forts to control both the land and the trade on the Nile. Goods from Upper Nubia and beyond were moved by boat on the Nile, including ebony, ivory, spices, exotic fruit, live animals, and skins, as well as gold, diorite, and other minerals from various mines.

During the reign of Senusret III (c1878-1841 BCE) great importance was placed on Lower Nubia. He established a separate administration for the Head of the South, and a canal was rebuilt around the First Cataract at Aswan enabling easier access for troops and trading vessels to reach as far as Buhen and the Second Cataract.

Getting around the Second Cataract was more difficult.

Fort Mirgissa

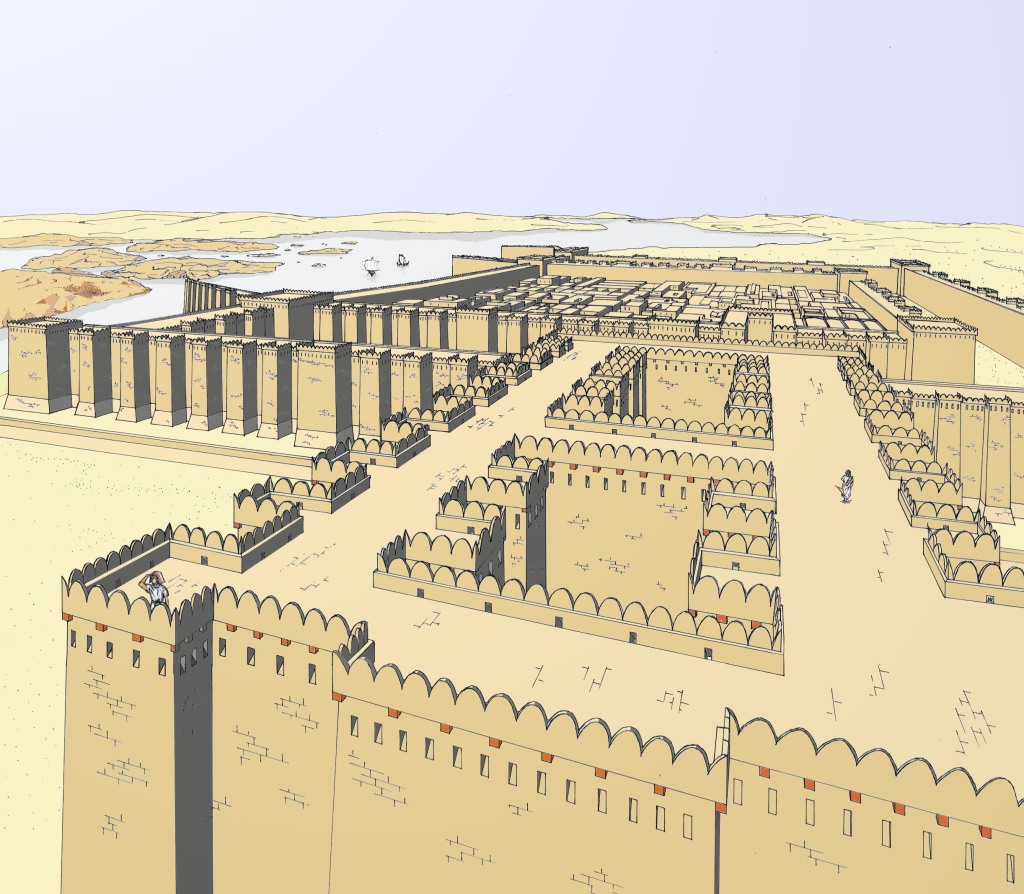

The Fort at Mirgissa was the largest of eleven Forts built by Pharaoh Senusret III during Egypt’s 12th Dynasty between the second and third cataracts. It was strategically placed above the cataract to control the River Traffic from the North, collecting revenues and taxes from all traders. Placed in the Western Wadi, the fort grew to 40,000 sq. meters. It was made of 10-meter-high mudbrick walls which were doubled to form a 6-meter thick outer and 6-meter-thick inner protective skin to the Fort, it had 12-meter-high square corner towers and numerous bastions for further protection.

After its construction, the fort also protected the harbour at the Northen end of Boat Slipway that run from the Nile below the cataract. Given that neither trade, exploration, nor war wait for the annual high waters needed for relatively safe navigation through the cataract, building the slipway to ensure safe portage was a prudent investment, of potentially great strategic advantage. The labor and resources invested to construct such an elaborate portage certainly indicates the significance of the traffic.

The Mirgissa slipway

The Mirgissa slipway is the only known example of its type. Conceived as a ‘boat road’, and constructed to avoid the least navigable portion of the Second Cataract, this structure allowed shipping movements all year. The slipway may have been built before the fort (the adjacent town is much older), and was used at least as late as the reign of Amenemhat III and possibly into the New Kingdom, a span of some 300 years.

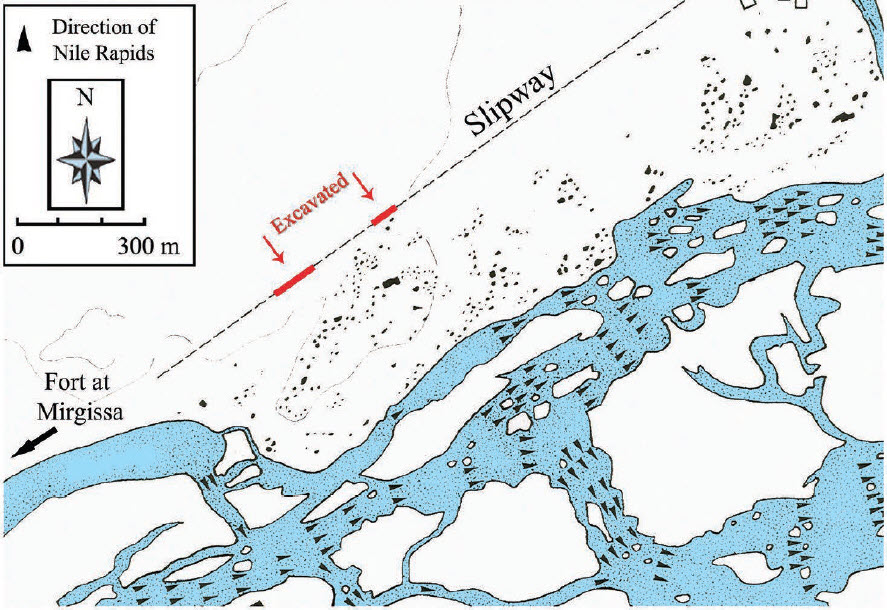

As mentioned, the southern (upstream) end of the slipway was in close proximity to the fort of Mirgissa (but which came first is an open question), while its northern end may have been at Matugaor Abu Sir. This means the slipway ran straight for no less than 1.5 and perhaps as much as 4 km.

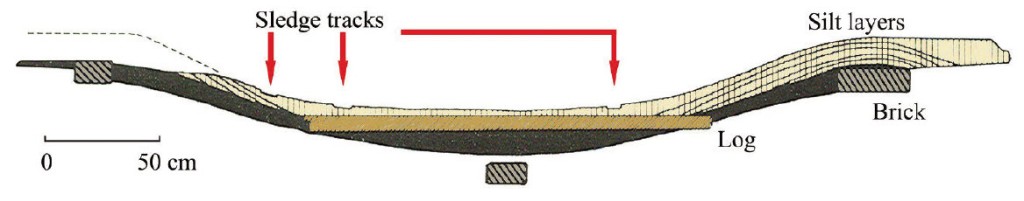

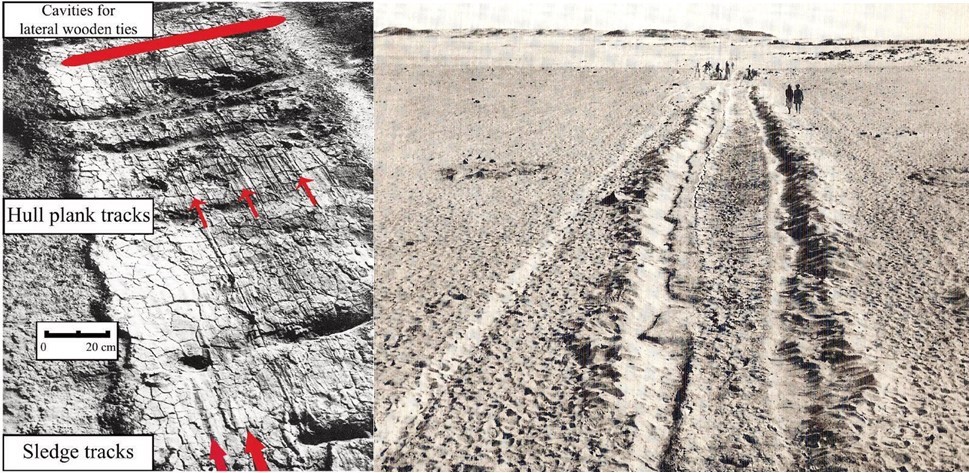

The slipway had a support structure of mudbricks, packed mud, and lateral wooden ties ‘rather like a railroad’, but remained low enough to benefit from the wetness of the silt to allow the boats to navigate the Slipway more easily sliding on the wet mud and timbers.

The slipway is approximately 3m wide, more than enough to accommodate the maximum beam (width) of the Twelfth Dynasty Dahshur boats (2.15 – 2.43 m) and would provide ample clearance for the width of a sledge. Both boat hull marks, and sledge tracks are evident on the excavated section of the slipway, these last travels baked into the watered silt road:

Why the portage stopped being used is unclear, the Second Cataract remained a major shipping hazard until submerged under the waters of Lake Nubia, created by the Aswan High Dam some 3,500 years later.

Conclusion

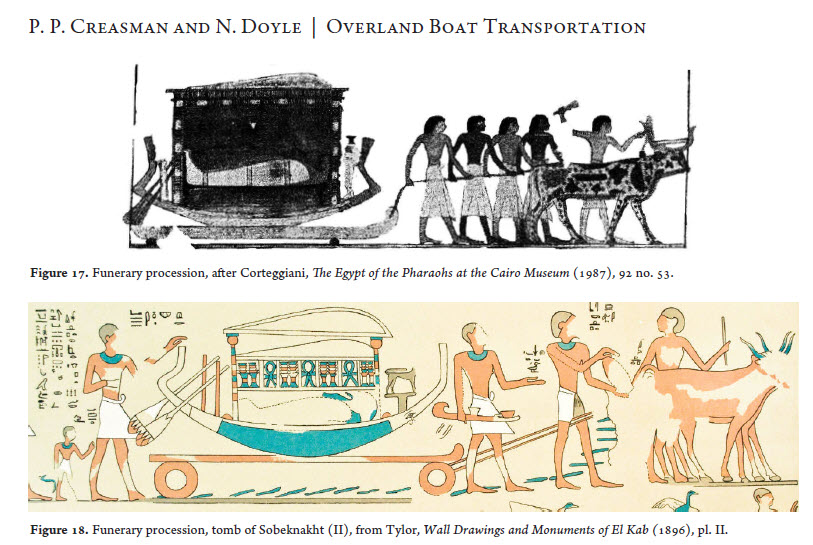

The correct answer to the question posed at the start of this article is unknowable. While the Diolkos may have been a parallel development with no outside influence, we know the Ancient Greeks and Egyptians traded across the Mediterranean and ideas travel with trade. We also know the Ancient Egyptians used both sledges and wheeled carts to move boats across land as part of their funeral rites and there is evidence of carved ruts being used to guide 4-wheeled carts in Malta well before the Diolkos was built.

What is not knowable is if Greek merchants or travelers made the journey up the Nile in the time of the Middle Kingdom and/or if the idea of man-made portages had wider currency and were a normal concept at the time.

From our perspective, there seems to be very few truly original ideas. Synthesis and elaboration are two of the key components of most innovation and there are very few completely original ideas.

For more on innovation see: https://mosaicprojects.com.au/PMKI-PBK-005.php#Process3

Primary Refences:

Overland Boat Transportation During the Pharaonic Period: Archaeology and Iconography.

Pearce Paul Creasman, Laboratory of Tree-Ring Research, University of Arizona

Noreen Doyle, Institute of Maritime Research and Discovery

Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections | http://jaei.library.arizona.edu | Vol. 2:3, 2010 | 14–30

Retrospect Journal (Edinburgh University):

https://retrospectjournal.com/2020/12/13/the-second-cataract-fortresses/